Cat (Weeden) Boye grew up with military roots. Her grandfather, Dick Weeden — a Brodhead native — served as Crew Chief in the Air Force during the Korean War. Her dad, Mike Weeden, went on to serve as a KC-135 pilot during Operation Desert Storm.

“I was in first grade when 9/11 happened, and I remember having classmates whose dads were guardsmen and reservists that deployed in support of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 2000s,” said Boye. “I had teachers who were veterans and even knew female veterans in the community. I thought joining the military was a normal thing to do at some point, even as a woman.”

She knew she wanted to become a military officer but was too young to apply to the Air Force Academy so, at 17, Boye chose to commission through Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). She joined Air Force ROTC in 2012 — as a Baylor University freshman — and had four years of officer training while in school.

In May 2016, she was commissioned as a second lieutenant and sent to Intelligence Officer training at Goodfellow Air Force Base in Texas. Boye went on to serve at Fort Hood, leading a team of Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Liaison Officers (ISRLO) who “provided intelligence advising and training” to the aligned Army units.

James Cassidy also followed in familial footsteps, though not intentionally at first. Cassidy is familiar to many in Monroe, teaching social studies with the Monroe School District. Before he began serving students, he was serving the country as a member of the United States Army.

“My dream since I was a little boy was to grow up and join the Local 139 Operators Union to be a heavy equipment operator/road builder,” he said. He graduated from Brodhead High School in 1996 and was unable to get into the union right away but remembered that his dad had worked as a heavy equipment operator during the Vietnam War era. After a school visit from an Army recruiter, he began to consider following his father’s example while both serving his country and learning the trade.

Having grown up in Brodhead and Blanchardville where “everyone looked like [him],” Cassidy says he didn’t fully understand the country’s diversity until he entered basic training — boot camp for military service.

“During basic training, I was buddied up with a ‘battle buddy’ from Virginia, and another guy from Texas,” he said. “That aspect alone, being immersed with Americans from all over our great country, was so eye-opening for me. I believe it is the best thing to happen to me with my military experience — to realize how diverse our country really is.”

Deployment

Boye deployed to Iraq from 2018 to 2019 as the ISROL for Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve, supporting ground units in Iraq with planning and executing their intelligence collection. She considers the deployment the highlight of her career, one she both hated and loved.

“This was after women were allowed to join combat career fields, but one of the units I supported was still all male,” she said. “Sometimes I would be the only woman in the room.”

She kept in touch with family back home when able and even enjoyed the occasional home comfort, like a showing of Captain Marvel hosted by the USO.

“Something about watching a free movie while eating the super discounted expired candy from the Exchange and sitting on a hard metal chair was really enjoyable,” she said.

One of the downsides for Boye was the heat and “the air smelling like burn pits and dust.”

While deployed, she was able to work with service members across generations, including a senior non-commissioned officer (NCO) in her unit who had been to Iraq in 2003. She remembers he missed both his daughter’s birth and her 16th birthday due to deployment.

“It was crazy to think about the fact that some senior service members have spent their entire careers supporting our ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and those conflicts have spanned the lives of their children and the evolution from landlines to cell phones,” she said.

Cassidy served in the U.S. Army from 1996 to 2000, until he was honorably discharged. As many service members do, Cassidy says he distinctly remembers the experience of arriving at boot camp when an enlisted member “comes on to the bus and says ‘You have 30 seconds to get off this bus and 29 are already gone!’”

“I thought, ‘Holy cow. What did I get myself into,’” he said.

Despite the chaos and culture shock, Cassidy was determined to make it through boot camp. He even surprised himself by how quickly he adapted to months of 4 a.m. wake-up calls and grueling physical training, like long runs or 12-mile hikes wearing full battle gear.

He attended basic training and AIT Job Training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and was sent to Schofield Barracks in Hawaii for his permanent duty station. He served as a 62 Echo — Combat Heavy Engineer/Heavy Equipment Operator. Upon arrival in Hawaii, he was assigned a semi, a lowboy trailer and a D7 dozer.

“It was my responsibility to keep up with the maintenance of this equipment in conjunction with our company’s mechanics,” he said. “I enjoyed the challenge of hauling heavy equipment with my semi and trailer and was often given tasks to haul all sorts of items around the island of Oahu.”

They also often trained in battle maneuvers, including marksmanship, loading equipment and training to fix roads at training sites. Cassidy says that, once a year, their training included “living in the woods in tents and training as though we were in a combat situation.”

While enlisted, Cassidy spent a four-month deployment in Tonga to help a construction platoon build a local village’s community center. He later deployed to the Annette Island Indian Reservation in Alaska to help construct a road across the island, where he said there were “more bald eagles per square mile than anywhere else in the U.S.”

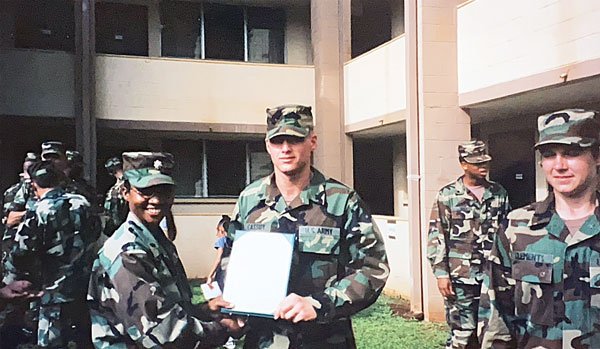

Cassidy tried to deploy as much as possible because he “wanted to experience everything that he could” during his enlistment. Upon earning the rank of E-5/Sergeant, he became a squad leader for 4-8 soldiers, in charge of receiving orders and guiding the squad members to carry them out.

A new perspective

Boye said her perspective as an Air Force veteran has given her a new shared experience with her dad and brother, one that has strengthened their relationship.

Boye’s brother, Robert, enlisted in the Air National Guard around the same time she started ROTC, leading their time in active duty to overlap.

Her dad administered her oath during her commissioning ceremony and pinned on her rank when she was promoted to Captain. She and her dad are technically both classified as veterans of the Gulf War era.

“My dad was my role model growing up, so it was neat to share some career milestones with him,” Boye said. “We deployed to the same area almost 30 years apart.”

The meaning of ‘Veteran’

Boye returned to Fort Hood, Texas, in 2019 and was selected as the Executive Officer for the 3rd Air Support Operations Group in 2020. She remained in that role until separating from active duty in June 2021 and went on to pursue her MBA degree.

She says she used to think that being a veteran was ‘normal,’ not realizing that the status puts her in a group of only about 7% of Americans — even fewer of those being female veterans.

“I’m proud to be a veteran and thankful for the service of all of my fellow veterans,” she said.

After being honorably discharged from military service, Cassidy finally got into the operator’s union and was on track to achieve his childhood dream. However, lasting pain from a hard fall during morning exercises while enlisted — leading to a back injury — cut that dream short.

His adjusted career path led to higher education, pursuing a degree in history and social studies to become a secondary education teacher. Skills and habits from his time in service carried over into his civilian life. He acknowledges that his students might describe him as “strict.”

“I do not particularly care for people being off-task when there is a job to do — like the day’s lesson or assignment,” he said. He also continues to be regimented, enjoying routines, walking fast, and even eating fast like they were required to do in basic training.

He also recounts his fellow “buddies” from his service in Hawaii as “some of the closest friends [he’s] ever had.”

“We became each others’ family,” said Cassidy. “It was tough to leave them when my four-year enlistment was up. I’d love to be able to hang out with them again and rehash old stories.”

Physical memories of his military time have also stuck with him. He continues to deal with severe arthritis of the lower back from that fall and is considered a disabled veteran.

Cassidy says he never saw combat and has “never been one to inform people” that he is a military veteran. However, with time, he has come to appreciate his service.

“I appreciate all of the veterans who did see the ugliness of combat and conflict, who live with those memories,” he said. He is also thankful that increased attention is being paid to those who have struggled with things like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, moral injury, traumatic brain injuries and other lasting effects of time in service.

“I once said to a fellow veteran that ‘I only served four years,’ and his response was, ‘But you DID serve,’” said Cassidy. “That really stuck with me. I’m proud of my service and I’m thankful for everything I was able to experience and learn, and for the great people I served with.”