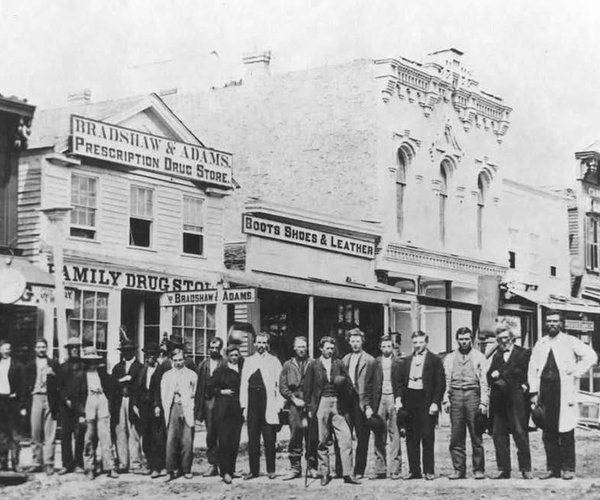

Only 10 days after the Great Chicago and Peshtigo fires on October 8, 1871, Monroe had its own fire on the northwest corner of the square where the Treat Block now stands. Although it was nothing in comparison to the other two fires, three stores burned to the ground, which resulted in about a $20,000 loss. Fortunately, no lives were lost in this fire. A photograph of the buildings that burned can be seen on page 40 of the Pictorial History of Monroe; that photo was taken in the 1860s before A. W. Goddard moved to the brick building next door.

The people of Monroe were called from their beds about 4:00 that morning by the loud alarms. “The destroying fiend” started in Bloom’s hardware store and was not brought under control until three stores had been leveled to the ground. Bloom, Allen, and Durst occupied those three buildings. Fortunately, E. Mosher had built the brick block (shown on page 38 of the Pictorial History) next to the south two years earlier, which stopped the fire from spreading to the rest of the wooden building.

The Sentinel sang the praises of the fire department as well as the generous aid given by the citizens. “Too much praise cannot be awarded to our Engine Company for their promptness and willingness to work.” The Hook and Ladder Company also received praise for their efficiency. The editor also mentioned that the engine, which the Board of Trustees had purchased in spite of the opposition, proved to be a success.

The Sentinel could not “refrain from mentioning” some individuals who deserved “the highest praise for their coolness and efficiency in rendering aid to extinguish the fire.” Jame Nee, ‘a trump,’ Sut. Norris, N. Churchill, Wm. Stout, and others of the Engine Company were named. The editor felt that Ed Ruegger and Sam Chandler deserved a promotion. “There were also a number of ladies who worked with a will, and deserve the thanks of all; there were also some that were not deserving of a large amount of praise, and we refrain from mentioning their names, as we have not room enough in our paper.”

The Sentinel shared the amount of losses and insurance information the following week, after the fire “left a blank space in the business of that thriving corner.” J. S. Bloom had a stock of $10,000, which he had insured for $3,500. He hoped to realize another $1,500 from what he was able to save. He moved to a building on the east side of what is now the 1100-block of 17th Avenue.

A. T. Witter lost about about $2,000 in eggs and other articles used in packing; P. Treat & Co. had an equal share in the business with him. Treat also lost two buildings valued at $5,000. A. T. Witter & Co. operated out of Treat & Co.’s grocery store for a time afterward.

Henry Durst lost about $2,000 in buildings and goods. By the following week, he had already opened his liquor store “one door west of Patterson’s Barber Shop.” By the same time W. H. Allen’s loss was still not known, but was believed to be small since most of his stock was saved. It sounds like he had been insured by Republic, who was “busted” in the Chicago fire. Within the week he had moved his stock of goods to the store “one door west of Union Block, north side of the Square, and is receiving new goods to stock up with.”

Three other business owners may have had their businesses in the upstairs of the buildings lost. Mrs. Cross, a photographer, lost everything and had no insurance. She sold her business to J. S. Busser the following September and left the following month for Little Rock. Mrs. Miller, a hoop skirt manufacturer, and Miss Adelaide Pool, a dressmaker, also lost everything.

There seemed to be some controversy about the cause of the fire, which was discussed in the October 25 issue of the Sentinel. Rumor had it that the daguerrean gallery (photographer) had placed a pan of ashes out of the window. It was later “positively asserted” that the fire originated from a defective chimney in the central part of the building where Bloom had his business. The editor suggested that people should frequently examine “the mortar joints and the foundations of these fire traps.” He also suggested that many people were being careless with “ashes, lighting matches about barns, and the unlawful use of kerosene and other combustible materials.”

Treat & Co. and Henry Durst announced only a week after the fire that they intended to build a new brick block on that sight the following spring. If weather permitted, they would lay the foundation yet that fall.

I found it interesting that the Sentinel included two articles about how fortunate Monroe had been in regard to fires on September 20, only two weeks before the Chicago and Peshtigo fires. The editor asked, “what would be the effect of a conflagration in the business part of the town on a windy night, undiscovered by any person until it had gained such headway as to be uncontrollable with buckets, and too hot for ladders?” He realized that there were still many wooden buildings on the square.

Another article from Harris Pool, president of the village board of trustees, mentioned that it was “the custom of many persons to attend without attempting to assist in any manner in the work of extinguishing a fire, but rather to stand in the way and obstruct the work of those who are willing to labor - when at the same time the few members of the fire department are worn out with their efforts.” He shared that a statute gives the board the “power to compel the inhabitants of their village to aid in the extinguishment of fires. Hereafter, whenever a fire shall break out in this village, all persons present will be expected to render such prompt assistance as may be required of them by the Chief Engineer of the Fire Department, and in case of refusal will be dealt with according to law.”

— Matt Figi is a Monroe resident and a local historian. His column will appear periodically on Saturdays in the Times. He can be reached at mfigi48@tds.net or at 608-325-6503.