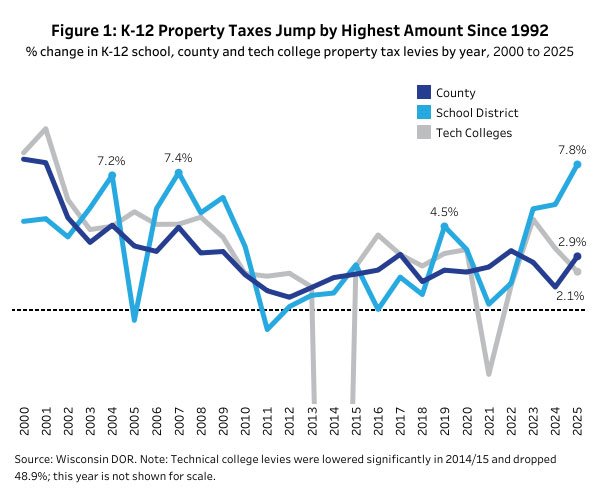

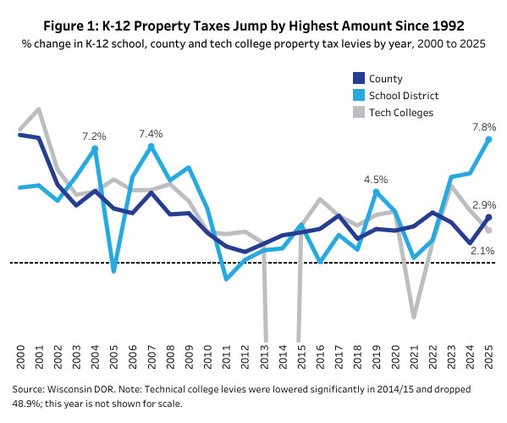

Gross K-12 school property taxes in Wisconsin are rising 7.8% on December bills, the largest increase in more than three decades. Local referenda as well as actions taken in the last two state budgets contributed to this jump. County property taxes are set to rise 3.1%, an increase more in line with recent years. As a net result, tax levies for all local governments are expected to see their biggest jump since at least 2018.

Property tax levies for all Wisconsin K-12 school districts combined are expected to rise by about $476.1 million to $6.58 billion on December tax bills, according to preliminary data from the Wisconsin Department of Revenue (DOR).

This would be the largest percentage increase since 1992 to these gross tax levies, which account for nearly half of all property taxes statewide. It also would be a significant bump from last year’s 5.7% statewide school levy increase, which at the time was the biggest annual increase since 2009.

The large increase in K-12 school levies is due in part to decisions in each of the last two state budgets, combined with widespread passage of school referenda in which voters authorized districts to increase their tax levies beyond state limits.

In this annual look at local levies, we review preliminary property tax data for school districts, counties, and technical colleges to give readers a sense of how their bills this year might look compared to last year. Data are not yet available for municipal or tax increment districts (TID), which make up the remainder of local property tax levies. The DOR data represent gross property tax levies, meaning they do not account for state credits that reduce net tax bills for Wisconsin residents.

State Budget freeze, Referenda Drive K-12 Taxes Higher

Three factors are the foremost drivers of this year’s increase in K-12 property taxes, starting with a provision of the state budget passed in July of this year. First, lawmakers and Gov. Tony Evers maintained the state’s increase in the state’s per pupil revenue limit on districts at $325 per year, a limit set in the 2023-25 budget through the governor’s partial veto. This limit governs how much school revenues can rise from the combination of general school aids and property taxes, which are districts’ two primary sources of revenue. This decision alone would likely have increased K-12 property tax levies to a degree. However, a second budget decision to freeze state general school aids also contributed to the record property tax increase.

Typically, a portion of the per pupil revenue limit increase is covered by rising state general school aids. Our previous research details the interaction between per pupil revenue limits and property taxes. Nearly every two-year budget over the past two decades has included at least one annual increase in general school aids, a form of aid that is distributed to school districts based on factors including property values, spending, and enrollment. This time, state leaders instead kept the funding for these payments flat, leaving property taxes as the sole means by which school districts collectively could access the allowed $325 per student increase.

School districts can choose to increase their levy by less than the allowed limit. Rising pressure on both revenues and expenditures, however, appears to have prompted many districts to levy at or near the maximum amount. These pressures include rising teacher salaries and inflation, revenue limit increases in recent years that lagged the rate of inflation, and decreased funding associated with declining student enrollment and the expiration of federal pandemic relief funds.

Districts did receive some additional funding through the current state budget, most notably via more than $500 million in increased aid to cover costs related to special education. The increase was intended to bring the state’s rate of special education cost reimbursement up to 42% for 2026, although current projections suggest that it may only cover 35% of statewide costs. This aid is not counted within revenue limits, so it did not limit districts’ allowable tax increases under the caps.

Taken together, these factors help explain why 28.7% of districts see a levy increase of more than 10% in 2025, according to the preliminary data. Figure 2 shows that, while the largest increases in total property tax levy would come from large school districts, property tax levy increases of more than 30% happened in both large suburban districts like Wauwatosa and small, rural districts like Bruce in north-central Wisconsin and Markesan in south-central Wisconsin.

Specific examples illustrate the underlying forces at play. The School District of Beloit levy nearly tripled, rising from $5.6 million in 2024 to $16.2 million in 2025 despite a failed fall referendum. This is largely attributable to a drop of $9.8 million in the district’s state general school aids, from $68.1 million to $58.4 million. The district can make up for this reduction by increasing property taxes to levy up to its total authorized per pupil revenue limit. The sharp rise in property taxes therefore does not represent a correspondingly sharp increase in core district revenue, which still only rose by the allowable increase under the revenue limit.

Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) is increasing its levy by $12.2 million, or 3.0%. While substantially smaller than last year, and a relatively small percentage increase compared to many other districts (the district ranks in the bottom third statewide in terms of percentage increase), the total growth is still notable. Last year, district spending and property taxes went up sizably due to voters passing a $252 million referendum in April 2024. In part because of those large increases, the state’s equalization aids formula allocated $104.9 million in additional state general school aids to MPS this year, which is an increase of 17.9% over the previous year.

The increase in aid resulted in a drop in the part of the district’s levy that is subject to revenue limits, which would have reduced property taxes for this year. Instead, however, MPS leaders chose to increase a different part of their levy, in a fund dedicated to community recreation programs, as they did in 2024. That part of the levy is not subject to revenue limits. The net result is that, instead of a drop in the property tax levy, the district saw the fourth-largest dollar value increase in the state.

Voters within Madison Metropolitan School District also passed large referenda in 2024, authorizing both capital and operating expenses, as discussed in detail in our brief on that district’s budget. Property taxpayers rather than state general school aids will bear the brunt of those increases, which this year amount to a $81.1 million rise in the levy in preliminary data. The district’s general aids also fell by $11.9 million, boosting the maximum allowable property tax increase.

Madison’s property tax increase alone accounts for 17% of the rise in total statewide K-12 levies. However, even without Madison’s increase, statewide tax levies would have increased by 6.9%, which would have been the third highest rate in the last 25 years.

Milwaukee and Madison were not alone in their use of referenda to increase revenue: The fall of 2024 saw the most referenda passed in state history. Then, voters in the spring of 2025 passed the most in an off year since 2015. The added impacts of the large number of referenda helped drive K-12 property taxes even higher than the 7.4% increase projected by the state Legislative Fiscal Bureau in July following passage of the state budget.

One additional factor that contributed to the tax increases was the growth in enrollment and payments for private school choice programs. Under the state’s complex K-12 funding system, growth in publicly funded private school enrollment can contribute to property tax increases. In addition, the 2025-27 state budget raised the amount paid per enrolled student in these programs, further increasing their impact.

In some years, increases in the state school levy tax credit and other credits can blunt part of the impact of school and local government property tax increases on taxpayers. However, like general school aids, the Legislature and Evers did not include any funding in the final budget to increase state property tax credits. This means that property owners will feel the full impact of these increases on net property tax bills.

County, Tech College, and Special District Levies

County levies are expected to jump by 2.9%, or $78.3 million, to $2.63 billion in 2025, according to preliminary data. This more than doubles the increase from last year, which was the smallest bump in more than a decade. County property taxes typically grow between 1% and 3% annually, putting this increase on the high end of the typical range in recent years.

Bayfield County (18.6%) and Forest County (16.9%) would see the largest percentage increases, while the two largest dollar value increases, Milwaukee County ($10.3 million, or 3.5%) and Dane County ($11.7 million, or 4.5%) also grew by more than the overall statewide increase of 3.1%. Five counties are reducing their levies, led by Juneau County’s 17.4%, or $4.0 million, drop. In comparison, 2024 saw 20 counties decrease their levy. Figure 3 shows how counties across the state changed their levies. We assume no change in the Menominee County levy, which is not yet available.

Continued inflation, the end of federal pandemic aid, and a smaller levy increase in 2024 are potential explanations for the larger bump in county property taxes. Growth in compensation for county employees also likely contributed to the need to increase levies.

Wisconsin’s counties have limited options for raising general revenues, with the property tax and local option sales taxes leading the way. Property tax increases are limited by state law, and sales taxes can only be imposed up to 0.5%, except in Milwaukee County, which has a tax of 0.9%. Most counties have already imposed a sales tax, with Waukesha and Winnebago counties the only remaining hold-outs. One of the few remaining tools for many counties is the local option vehicle registration fee, though more counties impose that fee each year.

Levies for the state’s technical colleges are expected to see the slowest growth of the three major property tax levies for which preliminary DOR data were available. They are going up by 2.1%, from $516.0 million to $526.7 million, trailing the 3.3% increase this year.

Taxes levied by special districts, local governments that provide specialized services like sewerage, sanitation, and lake management, are reporting levy growth of 3.8%. These districts would levy $141.6 million on December bills, with 84.2% of that total accounted for by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District. Fewer than half of all special districts levy a property tax at all.

Conclusion

Gross statewide property tax levies are on pace to grow by roughly 5%, according to the DOR data and Legislative Fiscal Bureau projections for the still unknown municipal and tax increment district levy increases. That would outstrip last year’s statewide growth of 4.4% and would be the highest since at least December 2007 tax bills (though not much higher than some recent years like December 2023). Given the lack of increases to state tax credits to offset the impact of these tax levy raises, taxpayers will likely see the full impact on their incoming bills.

At a time when housing affordability is a major issue, some taxpayers and voters will likely raise concerns about this year’s property tax increases. At the same time, however, state and local taxes in Wisconsin — including property taxes — have been falling as a share of personal income for decades and hit another record low in 2024. Given the massive income tax cuts included in the most recent state budget, and rising incomes, it is likely the average tax burden will remain relatively low (though effects for individuals will vary).

The income tax cuts represent a choice on state leaders’ part to prioritize using the state’s budget surplus to reduce some taxes instead of providing school funding to limit property tax increases (or increasing funding for other government services). This choice is in line with a trend since 2011 in Wisconsin of falling spending on K-12 education as a share of personal income. It also means that the responsibility for paying for local government services, especially schools, is shifting more heavily to property taxpayers this year than it otherwise might have.

On the one hand, this shift gives local school boards and voters control over their preferred level of taxation and spending. On the other hand, it also risks a widening gap in education funding between districts in which residents have the capacity and desire to pay higher property taxes, and those that do not.

Given the 2025-27 budget provisions and ongoing school referenda, it’s possible and even likely that next year will see tax increases of similar magnitude. State law will provide another $325 per pupil revenue increase but again no increase in state general school aids or property tax credits. The increase in special education aid will also be smaller than this year. Absent some special action by the state Legislature and governor early next year, property taxpayers will likely see more of the same in December 2026.

In the past, repeated tax increases of this magnitude have resulted in policy shifts in Wisconsin. In response to a run of nearly 8% annual increases to the statewide K-12 levy — and higher county and municipal levy increases — in the early 1990s, state leaders instituted a number of legislative changes, including the creation of per pupil revenue limits and a goal of two-thirds state funding for schools. With these provisions no longer limiting property tax increases as successfully, policymakers may find themselves revisiting the question in upcoming years.

— This information is provided to Wisconsin Newspaper Association members as a service of the Wisconsin Policy Forum, the state’s leading resource for nonpartisan state and local government research and civic education. Learn more at wispolicyforum.org.