A tragic accident that happened two miles west of Monroe was reported in the Monroe Sentinel on May 25, 1870. The paper reported the circumstances as best as they could at the time. Lewis Ellis, of Jordan, and James Grant, of Adams, were driving home from town, each with their two-horse team. Ellis was in front, with Grant coming up behind him at full speed to run around Ellis and his family. The team Ellis was driving became unmanageable, ran away, upset the wagon and threw Mrs. Ellis and their seven-month-old child upon the ground. This crushed the side of the child’s head in a frightful manner. Fortunately, nobody else was seriously injured. The child died the following day and was buried the day after that.

People who witnessed the incident all declared that Grant was responsible for the accident. “He was on a ‘bender’ while in town, and perhaps took on a heavy load of chain lightning just before starting for home, ‘as the manner for some is’ who visit Monroe on Saturdays. It is said that Ellis called back to Grant and told him not to drive as fast, as [Ellis] could not hold the horses. But when whiskey is in, humanity is out; on [sic] rushed the team, and then came the fatal crash that sent another human being out of this world and added another count to the indictment against that most damnable traffic, which has hurried so many victims to a premature grave. Let it be known that whisky was the cause of this murder!”

I didn’t see anything more printed in the paper about this incident, nor any kind of lawsuit against James Grant for this incident.

Just more than twelve years later, on October 14, the Monroe Sun reported that the same James Grant, well-known farmer from Shook’s Prairie, had been thrown from his wagon the previous evening and instantly killed. He had been in Monroe again and his neck had been dislocated by a wheel passing over it.

Information about the funeral appeared in the Sun a week later with more information about the accident and some editorializing. The funeral, with a procession of more than 150 teams, was one of the largest ever seen here. The remains were buried in the Monroe [Greenwood] Cemetery since burial in the Catholic cemetery was refused because he died intoxicated — even though he owned a lot there.

The editor stated, “It may be truly said of ‘Jim,’ as he was familiarly called, that he was his own worst enemy. He was a man of generous impulses and honest, whatever his weaknesses may have been in other respects. In his younger days he was temperate, but he gradually strayed from the path of temperance until he became what may be termed a periodical drinker. Had he let liquor alone, he undoubtedly would have been alive and in full vigor of health today. On several occasions he endeavored to break from his habits, but they had secured such a hold on him that he has often failed. Resolutions and temperance pledges were alike broken. We do not mention these things to dishonor the dead, but that those who are following in his footsteps may take warning lest they, too, be brought to a violent and untimely death.”

They also followed this with more of an account of the tragedy of the previous week. They shared that the last time that Grant had been seen alive was at Artis McBride’s. At this place, Grant was “so far gone in intoxication that he fell out of his wagon.” Some of McBride’s men helped him into his wagon and started him toward home. Grant was not able to guide the horses so they turned off the road at Diddlemeyer’s, from whom he had purchased one of them. Following that smaller private road, they traveled across an embankment, where the horses and wagon turned a complete somersault and landed on their backs. The tongue broke, which set the horses free; they were found the next morning still hitched together. When Grant was found the next morning, his wife was summoned to identify the body. One side of the wagon box laid across his neck; his death was instantaneous.

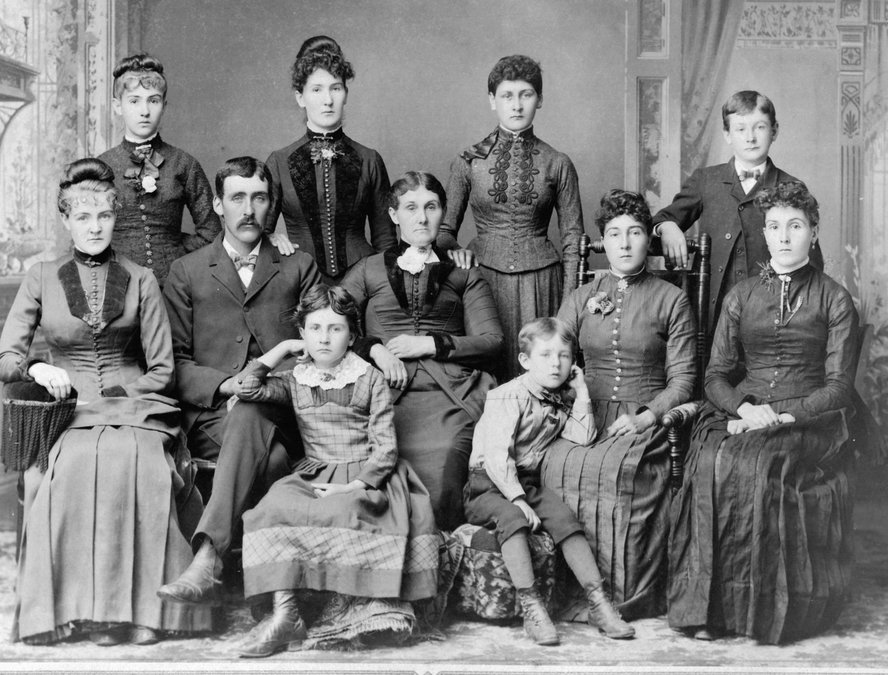

I came across the second article before I knew about the 1870 incident. I remember reading it for the first time with mixed emotions. You see, James Grant was my second great-grandfather. I wondered why McBride’s men would have put him back in the wagon knowing that he was incapable of driving the team home. I wondered what happened to James that made him rely too much on alcohol. This left his widow with eight of their twelve children still living with her on the mortgaged farm; the two boys were only six years old and six months old. The widow’s father foreclosed on her mortgage a few years later, which forced her to purchase a home in Monroe and move her family there. The widow lived in Monroe until 1909 when she passed away and was buried next to her husband.

— Matt Figi is a Monroe resident and a local historian. His column appears periodically on Saturdays in the Times. He can be reached at mfigi48@tds.net or at 608-325-6503.