Tina Duemler opened her new art gallery in December 2025 on the south side of the square at 1604 11th Street. Many people (of a certain age) might remember that it was the Miller Jewelry Store for many decades. After I started to research to write this column, I found two surprises. First of all, I didn’t realize that the original owner, Albert Miller, was a son of Anton Miller, the man who converted his furniture shop into the City Hotel [now Suisse Haus] in 1879. I also didn’t know that Miller purchased George King’s jewelry business after his death; King’s business dated back to the 1850s.

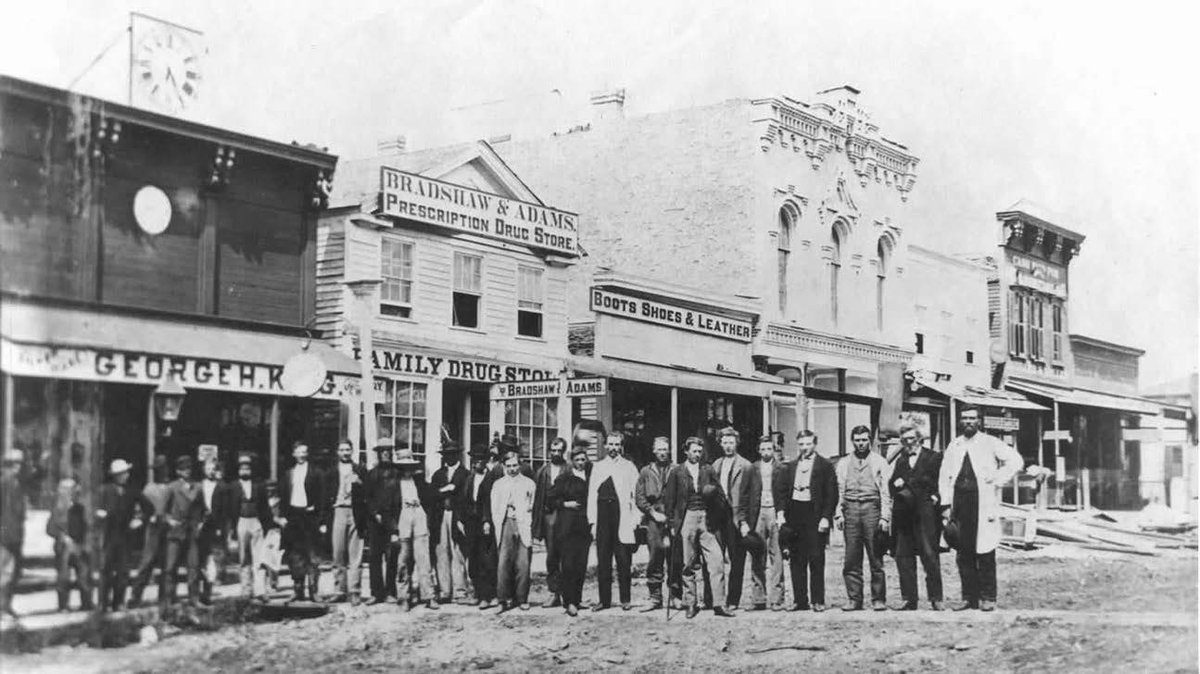

George H. King was born in 1822 in Youngstown, Ohio and came to Monroe with his wife and son, Charles B. in the mid-1850s. He was hired by jeweler James S. Wilkins, who had a jewelry shop on the west side of the Square. Henry Rowley was also employed there. Eventually King & Rowley succeeded Wilkins in that shop. It appears that they moved to the east side of the square by 1857. Sometime after 1859, King became the sole proprietor. [There are several references to Mr. King in Becoming a Village: Monroe, Wisconsin in the 1850s.]

King moved his jewelry store one door north of his old quarters in 1864. This store gave him more room for displaying goods. “A glance at his stock will convince anyone that there is no need of going out of town to find a good assortment of jewelry and all articles usually kept in stores of that description.” An advertisement on March 16 said that he carried American and Swiss watches, toys of all kinds, berry dishes, cake baskets, napkin rings, fancy goods, and Yankee notions. He also carried Steinway & Son’s pianos, Geo. A. Prince & Co’s melodeons, guitars, violins, banjos, drums, and fifes. In addition, he also repaired clocks. The editor shared that Mr. King “has fitted up his new store with much taste, and it is a real pleasure to step in and look at it.”

The 1870 census showed the couple, ages 48 and 50, living in Monroe with their children, Charles, 25, also a jeweler, Clara, 18, a music teacher, and Fanny, 16. Their real estate was valued at $2,000 and their personal property at $6,000. An advertisement in December showed that organs valued at $225 and $250 were reduced in price by $100. These organs were “finished in the best style” and warranted for five years.

An advertisement in April 1871 mentioned the “sign of the big watch.” This advertisement shared that he also carried sheet music, “the celebrated diamond, spectacles,” the Howe Sewing Machine, “needles for all small machines,” and “sewing machine oil of the finest kind, in bulk or by the bottle.” He also carried walking canes, microscopes, and accordeons [sic].

King announced that he would open the “Musical Society’s rooms” on November 15 “for the purpose of receiving scholars who may desire to unite with his class for instruction in the elementary branches of music.” It stated that the terms were reasonable and that it was “a good opportunity for those who wish to learn vocal music.”

In 1875 “George had a narrow escape from a fever siege,” but was able to be “about his business again” by May 26.

In a lengthy article on December 15, 1875, King described the stone cameos in fine gold, which were “worn by ladies who can afford to purchase them.” He carried brooches, earrings, and finger rings. They were very expensive because “the figures on the stones are cut by artists, and are as nearly perfect as possible.” It took a number of days to cut the small heads. They were then “set in find gold mountings by skilled workmen.” Previously, cameos were made from shells and were cheap. At that time the brooch and earrings cost from $30 to $50 per set, with the better grades ranging from $60 to $250 per set.

An article in May 1876 said that he was selling Elgin watches and gave some prices. A solid coin silver case warranted by special certificate from the Elgin Watch company was priced at $11.50. A solid coin silver hunting watch with open face was $13.50. The extra superior American watch, that had sold a year earlier for $115, was offered for $40 in 1876.

In September 1878, he reminded people that he could take their knives, forks, and spoons and, with the aid of a battery, make them silver-plated. “All my work will be warranted to give satisfaction, and last as long as the original plating did.”

King announced in the Sentinel on Saturday, October 3, 1880 that he had received, “a sample cabinet organ, the finest, best, and most beautiful organ ever brought to this country.” It could be seen at his home and was on sale “on time, or for cash.” At that time, Mr. and Mrs. King were living on the southeast corner of 16th Avenue and 17th Street; he was a watchmaker and jeweler. In May, King was “in the depths of misery” because he was having the store re-papered, painted, and frescoed, embossed, gilded and kalsomined by “Koken’s force.” The editor added that, “The agony will soon be over.”

It was shared on December 19, 1883 that King had “joined the temperance army, and united with the Temple of Honor.” He decided “to take this step after mature deliberation, and he tells us it is for life, and his many friends will help him to keep his resolution to the end.”

King shared in October 1886 that an optician wanted to introduce “his solid gold spectacles in this county.” Anyone who left an order with him that month would receive a pair of “solid gold spectacles” for $2.50 per pair for up to 12 pairs. That price represented less than the cost to the maker.

In the next column it will be shared how much longer the King jewelry store operated and what happened to King’s merchandise.

— Matt Figi is a Monroe resident and a local historian. His column will appear periodically on Saturdays in the Times. He can be reached at mfigi48@tds.net or at

608-325-6503.